Resilience Constellation interviewed Mikko Ollikainen, Head of the Washington-based Adaptation Fund, about their commitments, challenges, and ambitions.

No-one left behind

“In this rapidly changing world, adaptation is no longer a distant goal but an immediate necessity”.

These were the words of the Adaptation Fund Head, Mikko Ollikainen, at COP29 last November. His impassioned appeal in Baku, Azerbaijan for a global push towards climate resilience followed a disappointing year of pledges for the Fund, with just $133 million of the $300 million donation target raised by the end of 2024.

Since its inception under the UNFCCC in 2010, the Adaptation Fund (AF) has committed $1.25 billion to projects across the developing world, building the resilience of communities most vulnerable to climate change. With a claimed impact on up to 46 million people, the AF’s success stories include regenerative water systems in the Dominican Republic; adapting farming processes in Tanzania; and delivering crop diversification and soil management training in projects spanning Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe.

However, the Fund’s unmet pledges last year reflect a dangerous shortcoming of the international community. Adaptation has a critical role to play in protecting the world’s food security, water supplies, and agricultural productivity. As climate change increasingly impacts our farming systems, initiatives to boost agricultural resilience are more important than ever.

Despite today’s unstable geopolitical environment, Ollikainen remains confident in the AF’s mission to empower climate-vulnerable communities through strengthened international collaboration.

Discussing the Adaptation Fund’s evolution, enduring struggles, and future opportunities, Ollikainen explains what it really means to be climate resilient in 2025.

How have adaptation finance needs evolved over the Fund’s 18 years of operation? Ollikainen tells us that there is simply not enough to go around.

“…[A]daptation finance needs of developing countries are 10-18 times bigger than what is coming in through international public finance flows and the (Adaptation Finance) gap is as high as US$ 387 billion a year. This gap is also reflected in the Fund’s own demand – which has risen to almost US $600 million in project proposals that have not yet been approved or received funding.”

“The increasing demand is mainly driven by worsening climate impacts, sector-specific vulnerabilities, and the need for long-term, resilient solutions.”

More positively, Ollikainen highlights how growing adaptation finance needs reflect an improved global awareness of adaptation’s role in addressing climate change, and a deeper recognition of its social impacts.

“Countries are [today] better informed to make decisions on their adaptation priorities… While early adaptation priorities focused on a few main sectors, such as agriculture, water management and infrastructure, in recent years there has been a broader view to sectors, such as adaptation in health and education…”

“There is a growing focus on integrating adaptation and mitigation strategies side by side so that they can reinforce and complement one another, leveraging private sector investments, and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations, such as women, youth, and indigenous communities.”

When it comes to climate-vulnerable populations, Ollikainen is determined to facilitate empowerment over dependency.

The AF’s launch of a new funding window for Locally Led Adaptation (LLA) projects embodies this ethos, functioning on the premise that local actors “have the best understanding of their circumstances, and it is therefore crucial that all AF projects are informed by local knowledge. Putting local actors in the decision-making role empowers them to build their own resilience, which is essential for climate justice and for enhancing the sustainability of project outcomes beyond the project’s lifecycle.”

“One of the hallmark features of the AF is “direct access”, which means that developing countries can receive funding from the AF directly, using their own institutions to prepare and implement projects, rather than relying on the work or intermediation by international organizations.”

“From the Fund’s perspective, financing for locally led adaptation (LLA) goes beyond financial stewardship; it means delivering on the promise to empower local communities with both resources and agency.”

Representing almost 40% of the Fund’s total portfolio, agricultural adaptation is a key focus of the Fund. As of June 2024, projects in agriculture, food security, and rural development had received $474 million.

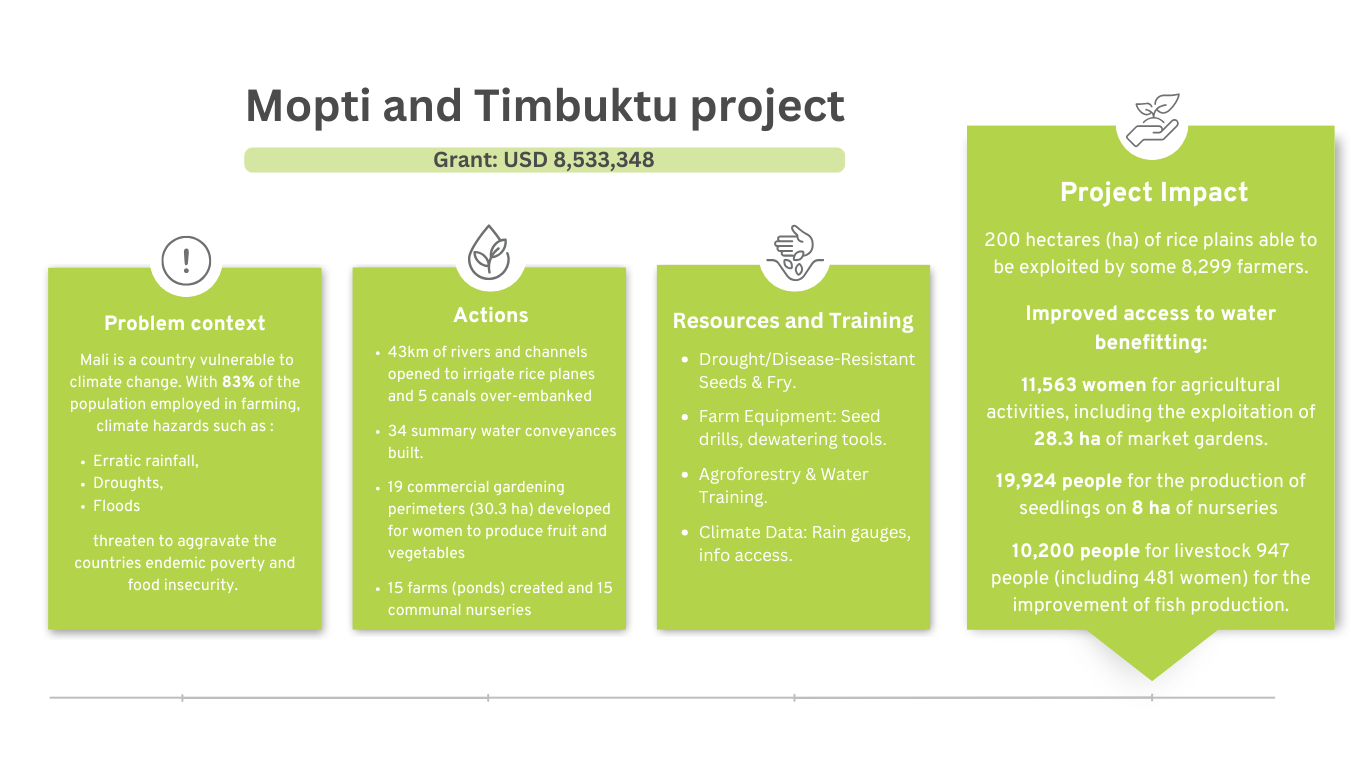

The “Programme Support for Climate Change Adaptation in the Vulnerable Regions of Mopti and Timbuktu” is one example of the AF’s agricultural projects.

Informed by local stakeholders, the project invested in both physical irrigation infrastructure and the training of 274 government officials and civil society teams.

Graphic created by Resilience Constellation, illustrating the Adaptation Fund’s Programme Support for Climate Change Adaptation in the Vulnerable Regions of Mopti and Timbuktu. Information source: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/project/programme-support-for-climate-change-adaptation-in-the-vulnerable-regions-of-mopti-and-timbuktu-2/

Collaboration is Key

Reflecting on the AF’s struggle to reach its COP29 pledge targets, Ollikainen emphasises the importance of international collaboration in climate adaptation efforts.

“The science of climate change is unequivocal in that the issue cannot be solved in the near term with the existing level of efforts. The long-term nature of addressing climate change calls for an approach that sources funding globally in an equitable manner…”

“The multilateral structure of climate funds like the Adaptation Fund is vital for achieving equitable and collaborative climate adaptation. It facilitates resource pooling from diverse contributors, enabling targeted support for developing countries and vulnerable populations, while promoting a cohesive international effort.”

“…[A]lthough it [COP29] did make progress, it was a struggle to raise more funds for adaptation… Contributor governments encounter competing national and regional priorities in areas like the economy and security, and geopolitical impacts of recent elections in some countries may also have had an ancillary impact.”

Challenges for 2025.

Ollikainen’s goals for this year and beyond include tripling the AF’s funding outflows and strengthening collaboration with similar climate initiatives, such as the Green Climate Fund, to, “enhance access to climate finance for vulnerable countries and scale up and multiply the impacts of (their) collective work while reducing duplication”.

The AF also anticipates a new source of financing, set to receive 5% of proceeds from carbon credit sales under the Paris Agreement. Revenues from a similar carbon crediting mechanism initiated by the Kyoto Protocol were crucial to the funds early years but dried up in 2012.

Resilience Constellation Analysis

In a new reality of dwindling foreign aid budgets and donations to the Fund, we are left wondering whether the AF’s current grant-based model of project finance is sustainable.

While locally led initiatives have many attractions, maintaining a growing portfolio of such projects can be like filling a bottomless pit, along with the risks of donor dependency and difficulties in demonstrating lasting post-project impact.

The agricultural sector should be responsive to properly-structured models of capital investment, with insurance playing an appropriate role in de-risking farmers’ investments.

By tapping into more private sources of capital, the Fund could build its resilience against an increasingly unpredictable geopolitical climate and widening Adaptation Finance Gap. With its experience, track record, and contacts, the AF is well placed to act as a catalyst for generating flows in the form of private investment and government loans.

Food security and the livelihoods of millions of farmers are too important to depend on a grant funding mechanism and unpredictable carbon trading proceeds.

By Olivia Cash and Richard Tipper