Alex Sage

Zero Hunger is the second UN sustainable development goal, and has three necessary steps to successful fulfilment: global food security, improved nutrition and the successful promotion of sustainable agriculture. Recent studies have, however, indicated that this goal is at risk due to global declines in crop yield.

The OECD has defined crop yield as the harvested production per unit of harvested area for crop products, usually calculated using production and area data. A recent FAO report highlights that, as expansion of agricultural areas contribute only marginally to increased production¹, yield is the essential factor to successfully boosting food production rates. Global population growth means that, for consumable calories per capita to remain constant, crop output must rise, placing further emphasis on yield to meet increased demand.

Crop yield has always been highly dependent upon climate and seasonal factors. Over 70% of agriculture is fed by rainwater², with many aspects of the food chain also being temperature-dependent. Co2 levels affect growth rates, acidification affects ocean-nurtured food sources and natural disasters such as flooding and storms threaten to damage successfully grown produce. Rapid environmental change places these crops at a real risk, not only of remaining static in terms of yield, but of declining to a point where the problem is further exacerbated.

What is the current measurable impact of crop yield on food security?

The proportion of the population affected by moderate or severe food insecurity rose from 23.2% in 2014 to 26.4% in 2018³, a figure driven upwards more recently by Covid-19.

Working specifically to understand climate impact upon yield, Deepak Ray and his team published results in 2019 indicating the substantial implications to date of climate change on global food production4. In a study of 20,000 political units of the top ten global crops the team used weather and production data to create a series of models.

- Climate change is likely responsible for ∼1% average reduction in consumable food calories across the crops measured.

- Impact varied by crop type, ranging from 13.4% decrease in oil palm to 3.5% in soybean

- Wide variation was also found between geographical regions, with predominately negative impacts in Australia, Europe and Southern Africa, largely positive impacts in Latin America and a variety of mixed implications across the whole of America and Asia.

The implication of these findings, as highlighted by their authors, is that climate change is not only a future issue for crop yield; it is having a very real impact now.

What are the future crop yield risks?

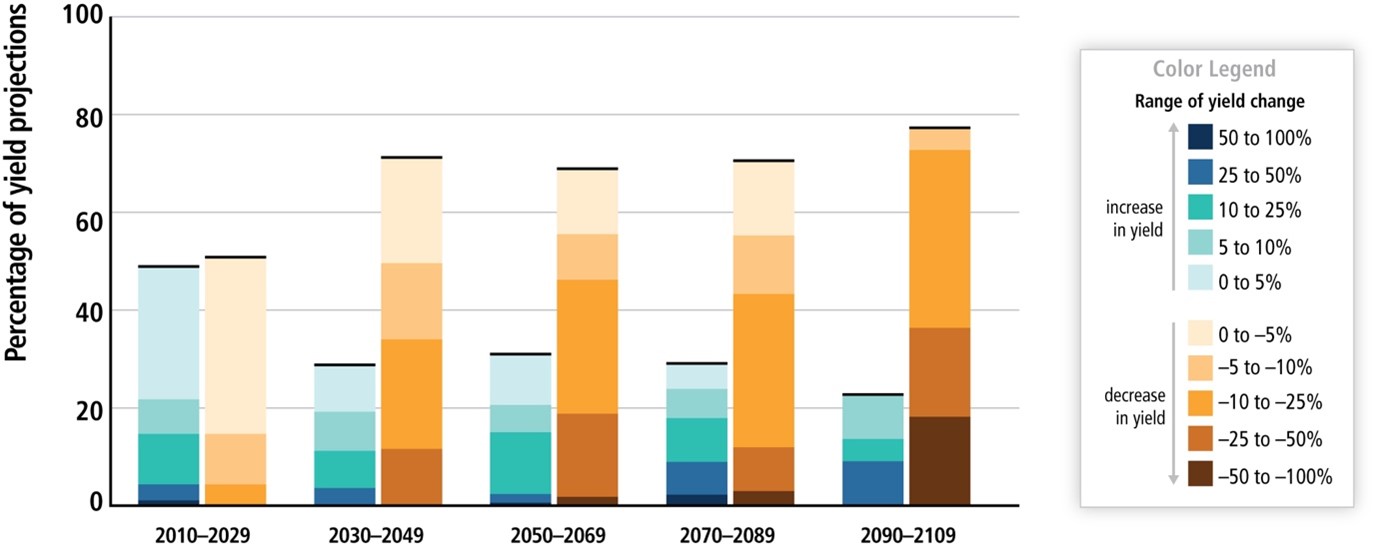

Yield projections published by the IPCC in 2014 demonstrate that negative impacts on average yield become likely from the 2030’s, with negative impacts of above 5% becoming more likely than not from 2050. Figure 1 demonstrates these projections, modelling a range of scenarios which include both those with no adaptation, and a range of incremental adaptations.

Figure 1, IPCC Report

The same IPCC report reviewed academic literature to demonstrate the likelihood of geographical shift within crops across the same period. Brazilian sugarcane and coffee are likely to move southward5, the former benefiting from increased temperature and Co26, whilst tea and coffee are expected to suffer at low altitudes, the former being expected to migrate upwards within countries such as Columbia7.

The practical implications of reduced crop access have been predicted to bring widespread price increases. IMPACT model analysis demonstrates the correlation between price and productivity, showing that doubling productivity across fruits, vegetables, pulses and poultry would potentially half the average global prices of the same8. A reduction of productivity would bring with it a corresponding rise in price.

Future opportunities for crop yields and food security

Projections of decreased yield constitute only part of the whole story surrounding crop development over the coming years. The varied yield of certain crops between countries demonstrates large-scale opportunity for improvement, and the potential for a substantial increase in food production at a global level.

Tomatoes provide an example of this, ranging from 4 tonnes per hectare of average production in Nigeria to 51 tonnes per hectare in China. Recent initiatives in Indonesia and the United Republic of Tanzania have successfully increased tomato yield by 20% respectively against control groups, demonstrating opportunity for focused innovations raising yield9

It’s important to note that varied research and academic sources often project varied contradictory yield development at a global scale. A recent study conducted in partnership between the OECD and FAO projects an increase in food availability per capita to 2029 to 3000 kcal and 85 g of protein each day, largely driven by a 9% growth in fats projected across the coming decade10. Whilst the study acknowledges a projected decline in staples across this time period, it paints a more optimistic attitude towards crop development, predicting a changing global diet rather than increased food shortages.

The same study asserts that yield improvement is the driver of 85% of worldwide crop output growth, with improved technology and practice allowing for far greater production than limited cropland expansion would allow.

How can we adapt crops to protect future food security?

Irrespective of projected yield and anticipated risks, there is widespread acknowledgement amongst national and international bodies of the need to implement adaptive measures, preserving the existing level of food security and improving this over the coming decades.

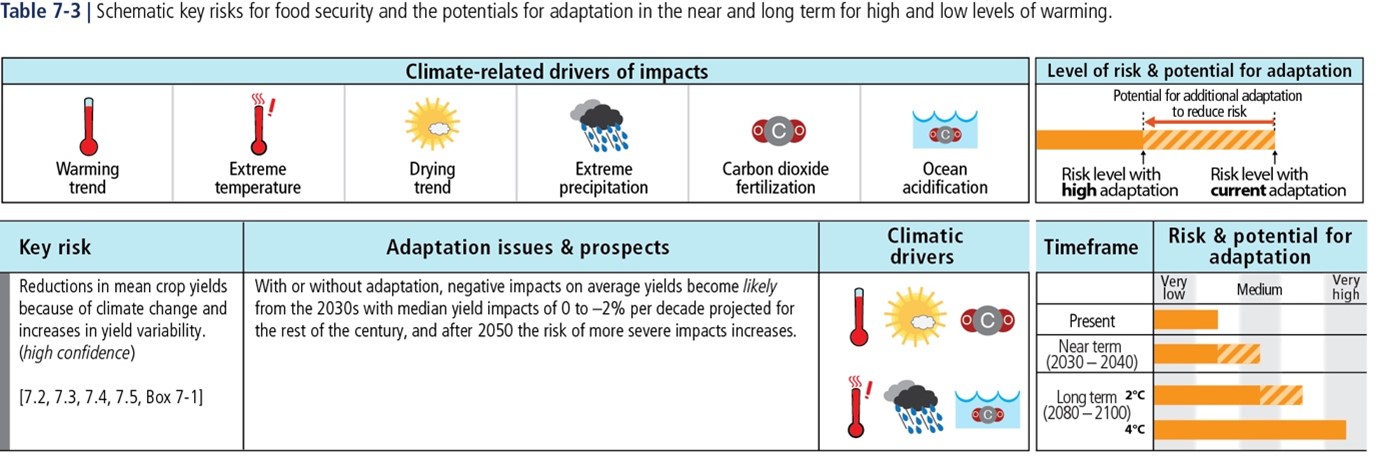

Figure 2, IPCC

As illustrated in Figure 2 high levels of adaptation, over and above current adaptive measures, reduce risk in both the near and long term. These measures increasingly focus on technology projects, with technological innovation driven by economic and institutional factors headlining many food security adaptation projects.

Food security is a key impact area which demonstrates the heightened requirement for collective responsibility to foster increased resilience to climate change. As yield is threatened and reduced across certain crops by the anticipated seasonal changes, technology must be successfully utilized to grow crop yield where possible and to implement the adaptation measures which will ensure global food security for the future.

Sources:

- FAO, State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, 2020

- IPCC, Food Security and Food Production Systems, AR5 Climate Change 2014,

- UN, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020,

- Ray et al. (2019)

- Pinto, 2007; Pinto et al., 2008

- Marin et al., 2013

- Ramirez-Villegas et al., 2012

- IFPRI. 2020. IFPRI IMPACT Webtool. In: International Food Policy Research Institute [online]. Washington, DC, as used by FAO in State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, 2020

- Gramzow, A., Sseguya, H., Afari-Sefa, V., Bekunda, M. & Lukumay, P.J. 2018. Taking agricultural technologies to scale: experiences from a vegetable technology dissemination initiative in Tanzania. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability

- OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020-2029, 2020